There are albums we hear, and there are albums that become part of us, etched into our emotional vocabulary like the scent of summer rain or the sound of someone we once loved saying our name. For me, The Joshua Tree by U2 was that album. At 17, still trying to map the borderlands of identity and possibility, I encountered it not just as music, but as a kind of revelation. It was less a collection of songs and more a soul’s desert pilgrimage, part elegy, part anthem, all vision.

Released in March 1987, The Joshua Tree was born from a band teetering between worldly success and spiritual searching. U2 had already tasted acclaim, but this album marked their transformation, from a post-punk Irish rock band into global torchbearers of something deeper, something mythic. They didn’t just write about America; they confronted it. They wandered its vastness, its contradictions, its ghosts, and made music that sounded like wind sweeping through canyons and firelight flickering on old motel walls.

I first heard it late one night, headphones on, in the darkness of a room I didn’t yet understand how to leave, or stay in. The opening drumbeat of “Where the Streets Have No Name” seemed to unroll like a ribbon of highway beneath a star-pierced sky. Bono’s voice didn’t sing to me, it lifted me into motion. The ache and promise in that track cracked something open. I didn’t know what “streets with no name” were, but I knew I wanted to go there.

The album is haunted and holy. It moves like a parched wind through yearning and injustice, faith and fury. “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For” is perhaps the most honest prayer I’ve ever heard, part confession, part defiance, fully human. It made me feel seen in my own youthful longing, my half-formed dreams and unanswered questions. At 17, that song was both a mirror and a map.

Then there was “With or Without You,” a song that bruised and healed in the same breath. It played like a slow-motion heartbeat, full of tension and surrender. At an age when love was still a mystery, beautiful, dangerous, terrifying, it felt like an echo of emotions I couldn’t yet articulate. It made longing feel epic, and heartbreak feel like an initiation rite.

But The Joshua Tree wasn’t just about interior landscapes. It was political, rooted in a hunger for justice. “Bullet the Blue Sky” burned with righteous anger, inspired by America’s role in the conflicts of El Salvador. “Mothers of the Disappeared” was a quiet, harrowing lament. These songs taught me that music could not only move you, it could awaken you. At 17, it helped me understand that to be alive meant not just feeling deeply, but caring deeply.

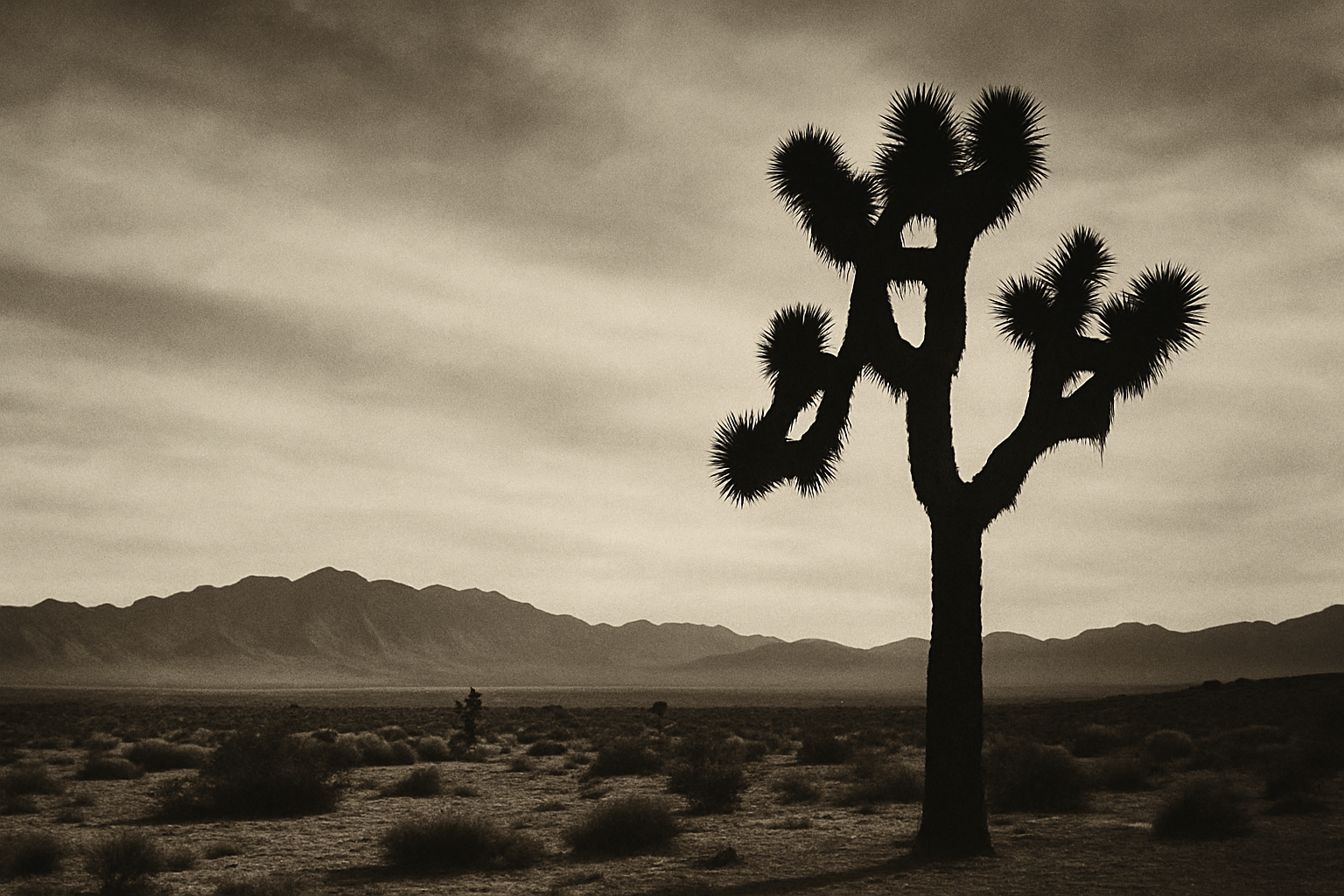

What made the album timeless, though, was its poetic vision. The desert was more than scenery, it was metaphor. A place of stripping down and searching. A place where silence and revelation met. Photographer Anton Corbijn’s stark black-and-white imagery, that iconic Joshua tree standing alone in a vast landscape, reinforced this mythic quality. It was less about the literal America than the idea of it, a place of promise and peril, of dreams and delusions.

And there I was, a teenager on the threshold of everything, seeing my own internal wilderness reflected in that music. The Joshua Tree didn’t just give me something to listen to, it gave me something to live by. It told me that beauty mattered. That searching mattered. That I could carry contradictions without needing to resolve them.

In the years since, I’ve heard countless albums. But The Joshua Tree remains singular. It’s the sound of dust and sky, spirit and shadow. It taught me that artistry could be spiritual. That truth could be sung. That somewhere, out beyond the edges of the map, there might be a place, a life, where the streets have no name.

And it made me believe I could find it.